Archaeologists recently unearthed the remains of a young adult buried 31,000 years ago in a cave called Liang Tebo. Surprisingly, the person’s left leg ended a few inches above the ankle, with clean diagonal cuts severing the ends of the tibia and fibula (the two bones of the lower leg). This is the oldest evidence of surgical amputation ever found—and it suggests that the patient survived for years afterward.

Clear-cut evidence for Stone Age surgery

We don’t know the young person’s name (archaeologists have dubbed the patient Tebo 1), and the bones offer no clues about biological sex. What we do know is that injuries must have been a common fact of life in the young person’s community. Hunting, especially in mountainous terrain, is a dangerous way to make a living; the bones of Neanderthals and ancient members of our own species reveal that people got banged up fairly often during the Pleistocene.

Although falling rocks or the chomping jaws of a large animal can definitely remove a leg, that kind of trauma crushes or shatters the bone. It doesn’t leave neatly angled edges—and the smoothly sliced ends of Tebo 1’s leg bones look like the work of sharp instruments in skilled hands.

The cuts also show signs of healing, remodeled bone that suggests Tebo 1 lived between six and nine years after losing the leg. Based on other skeletal clues, Griffith University archaeologist Tim Maloney and his colleagues estimate that Tebo 1 was around 19 or 20 years old at the time of death. And that means Tebo 1 must have been a child, between 10 and 14 years old, at the time of the surgery.

Growing up disabled in the Pleistocene

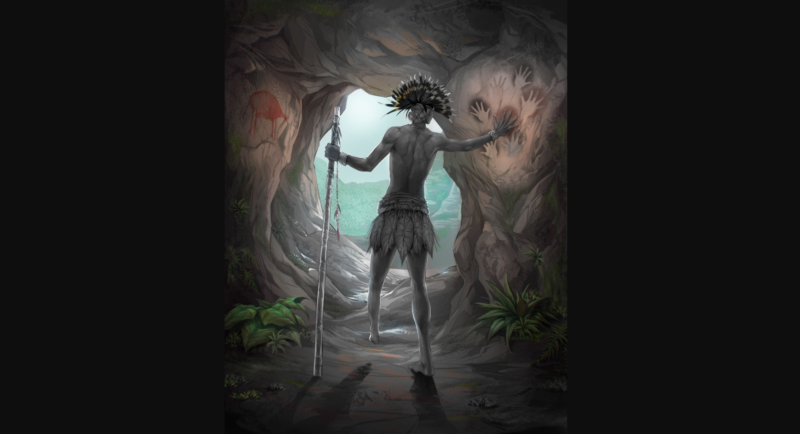

Imagine being a preteen or young teenager in Borneo 31,000 years ago. Your small community survives by hunting and foraging in the mountainous, cave-riddled tropical forests. And then it happens: You get an injury so severe that cutting off your leg offers the only chance of saving your life. Most likely, something has cut off circulation to your lower leg, some of the tissue is now smelly and gangrenous, and it’s spreading fast. What’s your prognosis?

Based on Tebo 1, that situation was less dire than you might expect, although it almost certainly wasn't easy.

For one thing, the severed leg bones show no signs of inflammation, which means that if Tebo 1 suffered any infection after the amputation, it wasn’t serious enough to reach the bone. Without antibiotics, infection is a major threat; most of the casualties in American Civil War field hospitals died of infection, not of their actual injuries.

The fact that Tebo 1 apparently didn’t face serious infection suggests that whoever performed the amputation understood how to keep the wound, the surgical tools, and their hands clean and understood that they needed to do so (which puts 31,000-year-old hunter-gatherers ahead of European and American surgeons just a century ago). It also suggests that someone took very good care of Tebo 1 after the operation.

“It is inferred that life without a lower limb in a rugged and mountainous karst terrain presented a series of practical challenges—several of which can be assumed to have been overcome by a high degree of community care,” wrote Maloney and his colleagues in their recent paper.

Tebo 1 grew up with one leg and not much mobility; the left tibia and fibula are thin in a way that suggests atrophy from disuse, and they’re smaller than the ones on the right, which probably means the bones of the left leg didn’t continue growing after the childhood injury. Meanwhile, even the right leg shows some bone thinning, which “suggests that Tebo 1 was rarely ambulatory, owing to the incapacitating nature of the injury to the lower left leg.”

But Tebo 1 did grow up, and that forces us to reconsider what we think we know—not only about what very ancient people knew but about how they cared for one another.

reader comments

61